Front Page

Discover a labyrinth of mysteries

Meet The Characters

Friends, foes, villains and victors

Navigating Metropolis

DISCOVERY

A century ago, when the old Regency College was established on the hill, our great brick building held the engineering school where Dr. Hartley Mills Thayer led the earliest investigations into chromatic depth projections, the frictionless turbine, mechanical men, and other critical discoveries. Down in the stone basement stowed among the furnace and utility equipment were dozens of thick wooden crates packed to the limit with obsolete electro-mechanical inspirations and apparatus. Persistent rumors of radioactive wonder gasses from ancient wave experiments creeping into our ventilation ducts apparently kept quite a few students away from our old building, which was fine with me because it meant less commotion on the floor at night and more hot water in the morning showers.

MERton-3457. That prefix served a sector in the soot-blackened Catalan District of industrial east metropolis, inhabited by dim constellations of the dispossessed and hardly noticed, where the golden people from brighter precincts often sneaked off to be stained. There, tall old brick tenement buildings, cold and drafty in the winter dark, became blistering steam furnaces by the dog days of August. Neglected sewers backed up hourly. Rude livery stables bred rabid legions of rats and scuttling cockroaches that prowled the disordered perimeters of ash and cinderblock, so near the immortal river that man and mongrel squabbled over organisms washed ashore in the grassless lee of empty encampments mourned over and abandoned by the world beyond. Rumors of bloodless cataclysms in packing-crate apartments, bone-dust spied on the ruptured floors of barren warehouses, sidewalks haunted by pale travelers and hosts, were whispered to the greater metropolis by leaflet periodicals and wounded refugees from the eastside underground.

Marco brought me into the undercity through a long corridor of brick and limestone lit by gas lamps. Nearer, we crossed a plank walk over a thin stream of water flowing beneath our feet from some obscure subterranean source. And then ahead, voices and light and a society not so different from that I’d known above. Freddy and I were wrong about that hell of rats and filth and sewer men inhabiting bleak, black tunnels, narrow and nasty. What I had expected to be gloomy mud and stone crawlspaces and narrow passages were, in fact, a vast tunnel network of understreets realized by banished architects demolishing miles of ancient limestone to build a reverse world inhabited by people our own great metropolis had given up on and forgotten. A web of disjointed dreams.

He raised his lantern high and led me off where pale grey ivory skulls were stacked so closely to one another there was hardly room for dust in between them. More awful than Doré’s illustrations of Dante. Here, as we walked the long hideous corridor maybe half a mile or more surrounded ground to ceiling by skulls and fragments of human beings, I witnessed that record, the decline of flesh and bone, humanity undone and reconciled to this subterranean cavern, the unfortunate and impure catacombs of our great metropolis. There were thousands of skulls and fragments of skulls, and skeletal remains, probably hundreds of thousands, a ghastly gallery of the dead, a true monument, even, to eugenical madness and horror. Farther on, I saw more recent skeletons nailed to skulls and decorated like Christmas trees with glass baubles and dried fruit, suspended like ossified saints among antediluvian bones. The deeper into this catacomb we walked, the more I began to suspect we were breathing dust of the dead, resurrected this hour in our lungs. As if we were inhaling the history of a race and its decline and death, its record of demolishment.

“Anchorites from the lower catacombs,” Marco told me. “They burn Ophian incense and sing prayers for the souls of lost pilgrims whose bones haven’t yet been found. They have sheltering camps on the banks of the dark river, Potamus, that flows beneath us to the bottom of the world. Have you heard of it?” “No.” “They say its source is rainwater from iron cells and old mine shafts, leaking out of cracked and rusty pipes in the cold earth of your metropolis, a guilty reward from God for having abandoned us. No one knows if it’s true or not. Castor and Pollux once told me that to those who inhabit the lower catacombs, your moon at night is a dreaming eye, of less substance than ‘dust on the wings of a moth.’ Down below are rumors of transparent children composed solely of light and air, and alchemists brewing liquid fire for rise and revolt, and some mysterious presence in the ancient coal pits.”

For those of you who have never stepped inside the Dome, I must tell you that it is inexpressibly vast. No arrow or crossbow bolt could reach the ceiling from the floor of the Dome. Its construction exists in the mythology of the Republic, a massive edifice erected millennia ago in another world bearing faint similarity to our own. Yet we worship its grandeur with far more reverence than any of our exalted cathedrals. On the great floor, rendered in solid gold on a tile sea of indigo blue, are the twelve signs of the zodiac, representing by metaphor we who are human, gazing up at a cosmos that is both indecipherable and never-ending.

The train rolled through towns, too, small and rural. A population of ordinary citizens. Country towns. This fertile ground fed and sustained us. These rural people were our saviors in times of want. We could not eat our polished marble, our gilded edifices, or ten million paper credits. How far from the wide boulevards of the metropolis did rumors of inferior blood carry? I watched the day pass in carted bushel baskets of potatoes, and iron tractors urged through growing fields by women and men in simple cotton clothing and sun-shading hats, and wondered if these people were considered useful citizens by the Status Imperium. Was their value found in that sacred humanity each of us shared, or only in those heaps of produce trucks carried from this raw earth to our hungry markets? Did spyreosis even exist in the labored blood of those who dug our planting furrows by spade and hoe? I hadn’t considered these questions before boarding the train to Tamorina. Worlds apart are often worlds unacknowledged.

The sky was dark now and there were lights across the last fields of Fabian Province. Next were forested mountains of Tarchon Province, what the map designated as Kumari Wilderness. No towns or villages. A stronghold for our indominable enemy forty years ago until we set fire to the entire forest with batteries of incandescent artillery shells enhanced by radioactive phenotheric gas. All life in that prehistoric wilderness ceased for almost ten years.

We arrived at Crown Colony late in the day, a vast encampment on both sides of the Alban River. Ten thousand tents crowded the embankments as far as I could see to the north and south. There was a strong bridge built across to the other shore, wooden shanties along the waterfront, boat landings abounding. When war came across the Fatoma River, forty years after the Great Separation, those simple rural people who had been inhabiting these fertile lands both west and east of the Alban River for quiet centuries were unprepared for the intrusion of hatred and persistent darkness. They were swept away almost entirely in those relentless waves of battery and invasion. No hint of them survives. Rumors have them escaping downriver to Xandro and Hippisia on the southern sea and beyond. Other opinions invite words like annihilation and extermination. No one knows for certain except that fate intervened and their legacy was diverted.

The Péridon Road was muddy and rutted and rough. Not so much a road those days as a wide passage in a great field of nothingness. Hard to see even whether it had been growing fields or grassy meadows or horse and cow pastures when the war and those constant bombardments arrived. Where our two-truck convoy drove east, I saw no trees at all. No ruins. No people. No birds. No life. There was nothing but mud clear to the rainy horizon.

My boots crunched on the icy snow as I strode forward. Rather than exploring the landscape or wandering off into the birch woods, I chose to follow the simple path tramped by those people I’d seen when I first awoke. The freezing air was so still, only my boots in the snow disturbed the morning quiet. That trail they’d stamped weaved through the birch trees which appeared planted as an arbor of sorts rather than any natural growth. I looked up and noticed the sky was still patchy clouds with only traces of blue. A light feathery snowfall persisted as I walked. I adored it. Even catching a snowflake now and then on my tongue as I went along. What was this place? So tranquil. My breathing and boots were all I could hear in the birch wood. The fog of my breath was delightful, and the scent of wet woods and frozen earth and leaves.

I found a wonderful library of perhaps a hundred thousand dusty volumes. The parquet floor was covered in rose and blue oriental carpets with mahogany side tables to a dozen leather armchairs and brass lampstands for reading. The wood ceiling was coffered in hexagons except in the center where a fantastic trompe l’oeil painting eighteen feet above portrayed Prometheus descending to earth with the fire that gave birth to civilization. So ironic, I thought, how we’ve used that flame throughout the Desolation to burn each other to death and torment the very world of humanity Prometheus desired to create. If that irrepressible Titan saw us now, would he believe the suffering he endured on Mount Elbrus had been worth his ceaseless agony?

Farther on we flew. Miles and miles. I began to feel strange, wondering where on earth we were headed. No one spoke. The carriage was still as we sailed through the icy night. Nothing but snow beneath us now as the white forest thinned and disappeared. Another mile or so, and I saw the strangest sight: a great expanse of blackness ahead on the horizon. Slashing across those snowy fields of our flight. Eerie and vast. As the airship approached, I thought we’d flown to the end of the world. Endless miles of snow quit there at a border of darkness. I felt scared at last. All along our flight, I knew we were hundreds of feet above the frozen ground, but I could always see where we were, almost feel the earth below. And now suddenly we had nothing beneath us. A true black void as we floated above that last precipice of ice and snow and the commander slowed the airship.

We were met in the Great Hall by a little fellow in a grey tuxedo and tailcoat. He was mostly bald and wore a white bow tie. He stood in the middle of an intricately detailed ancient Roman mosaic of the eternal zodiac that encompassed the entire center of the immense floor. Directly overhead was a coffered half-dome of gilded rosettes with a cove and swags of marble pearls and fluttering ribbons surrounding a frescoed ceiling oculus of Lord Jupiter on a chariot brandishing a handful of fiery lightning bolts. The image was grandiose and marvelously intimidating. I presumed it had either survived the great earthquake or been meticulously restored to a former glory.

Motor traffic was absent as I reached Opera Street and went up the hill to my left. There, the sidewalk was quite steep with shops on both sides perched at a curious angle. Too narrow for autos, the old cobblestone was wheel-worn from centuries of iron-wheeled carriage and cart. More fashionable clothes shops and exotic glassware. Oculist and cartographer. Florist and fortuneteller. A sculptor’s studio. Calligraphic art of placards and posters. Pastries and spice candy from Porceliña. A fancy dress establishment for ritzy clothing. From this splendid section of the metropolis, one couldn’t have expected the nasty, polluted streets of East Catalan. How do we breathe the same air, drink the same water, and live in such different worlds? Was it truly necessary to name the poor and downtrodden, the ill and disregarded, as our mortal enemies and exclude them from all the beauty and inspiration we enjoy? Couldn’t eugenics have led the more fortunate of us to enhance the lives of those whose mornings were not as full of sunlight and goodness? Do the happy truly need to exterminate the sad to remain happy?

I looked up the address for Jimmy Potatoes on Olivette Street. I hadn’t been there since freshman year and that night our taxi had gotten lost in the mazy streets, so I had no firm memory as to where it was. Somewhere in the crazy Beuiliss District where low-rent clubs and dine-wine-danceries flourished. Thrill-a-minute halls. Perfect for college students and energetic layabouts whose enthusiasms rarely extended much beyond liquor and late-night nonsense.

We had a good look at his little apartment with that metal cot and comforter, a small cookstove and a bar of soap in a water bucket for a sink. Rags for wash cloths. No windows. One wooden chair. A strip of worn-out canvas tarpaulin for a rug and a ratty little suitcase for keeping a change of clothes. The room smelled of sweat and mold and that not too distant wet sewer below. “Do you really live here?” Nina asked Marco, as she took the chair.

We went up the stairs to the second floor. A few of the treads were sticky and I didn’t ask what from. There were people in some of the rooms. Liquor was on the guest list. I couldn’t imagine what else. We beat the elevator and Marco led me down the hall to the fifth room on the left. He knocked twice in rapid succession, paused a moment, then knocked once more and went inside. I took a look down the hall as the elevator arrived, then followed Marco into the room. Dingy would have been a flattery. Drab peeling wallpaper, soot-stained and sad. A creaky nightstand with an old iron lamp, a ratty rug in the middle of the small square room. A metal tray of vials, one sea-blue and the other brown, and a pair of syringes. A pile of leather straps. And three bodies. One facedown on the iron bed. Two on the floor.

We arrived at the sewer beneath the old latrines. A narrow corridor had been cut through the sandstone, just wide enough to permit the huge crowd of children to escape down into the Faubourg tunnel. The machine that had carved it out rested off to one side in the dark, like some immense food grinder but without the handle. I saw the motor running, yet the iron contraption was almost entirely silent. A frictionless turbine. Only fresh dirt falling from its maw caused any sound at all. Very eerie. The area was thick with a foul-smelling dust. Dried excrement? Dead vermin? Sweat? Probably all of that.

I wondered how long I was expected to wander in this labyrinth of mysteries. Our vast Republic was neurotic and disproportionate in its duty to citizens across our varied provinces near and far. The war was more than disruptive and cruel to those without high leather offices at Prospect Square. Our imperious disgrace infiltrated the souls of so many people, young and old, among hundreds of disparate cultural origins and persuasions, how did we possibly expect to purge the epic disease of eugenical dogma that had been systematically inculcated across the decades throughout this nation of individuals? Was it even reasonable to imagine anymore? Because, when wars end, then what? Do all wounds truly heal? Does every pain and resentment die away in its own moment? Mr. Sutro suggested that generations must pass before such memories as our war against the unfortunates may vanish, even though vanish they will. And perhaps that’s true. Who would deny that hope? Yet what of us now? Was there truly light ahead? Where in this dark troubled labyrinth were those candles lit?

Trecéirea had a mild climate and a most cheerful and pleasant populace. The town where Nina and I settled with Delia and Freddy was called Musset. It was a small fishing village with pretty painted houses and crushed-stone streets. We lived in a green two-story house at the top of a lush tree-shaded lane a couple of blocks from the shore where Delia could walk Goliath to the beach and gather seashells for her bedroom collection. Our rooms were upstairs, and Freddy took his on the bottom floor off the kitchen facing a dooryard of orange and lemon trees. No one explained how we were able to be there, but we supposed it had been arranged for us.

LOVE

O love, sweet sanity’s orphan!

A girl smiles and her childish dimples tie our thoughts in knots of nonsense.

True love is the silliest of clichés.

Love is so terribly irrational.

Why is love so provoking of emotions that drain our will?

If this is called love, that kind agony would surely be my undoing.

Love isn’t one of our daily trials.

Whose heart do we trust? Our own, or our lover’s?

My first lessons in love: hurt and happiness. Both sides of life.

I felt a wave of desire, that brilliant flush we get when we allow ourselves to believe love has descended upon us at last.

Love is the most astonishing inebriation.

First love is an astonishment, the bluest of all our blue, blue skies.

Love is also a gamble. Sometimes it’s willing, sometimes not.

A lover’s fortune must include a best friend.

Love is both a blessing and a worry. Running by instinct is hopeless. Resorting to cold logic ignores our natural desires.

Love is both temperament and acquiescence, humbling and inspiring. The balance between these contradictions fires a universe.

Love is a blinding agent.

Is love forever entangling?

Love has no geography but what we believe and remember of it. Near or far, matters not. The heart may travel, but never leaves.

If there’s anything perpetually true in the trials of love, it’s that no one wants to be left.

Love is a most powerful inducement. Nothing in our world surpasses it. Without love, perhaps none of this has any meaning but storm and fire. Not enough to suffer for. Loyalty itself derives from the heart in terms of faithfulness which can only evolve from love.

The world poisons us if we don’t find our own antidote through beauty that survives the ugliness of our times.

Love means more than squandered virtue.

Love comes from trust.

Admiration arrives in many forms, as does love.

Love’s little intrusions make us whole when we had no idea we were not.

Making love is a waltz of souls

That desperate rationality of love.

I loved her without any good and true assurance of who she was, whether angel or wraith, and my heart refused to ask.

Do tears not flow from our hearts? That ache we suffer is as pure a sign as this world offers that we’re alive and meant to be here with those we love.

O, when our fond hearts freely/ by the willow trees dearly/ lead we young lovers along.

May these kisses lead my heart to you.

Our hearts are haunted by those we love, whether high in the heavens or down on earth.

Perhaps love creates and strengthens our bonds to earth and to those with whom we share it.

Our hearts have bottomless caverns of empathy when explored by love of more than ourselves.

Loving and being loved, forever the best part of life.

Our purpose, which is to love each other without reservation or fear.

Only love endures forever.

Life is solely concerned with love.

WAR

Sixty years of slaughter and mayhem, millions eradicated, history itself diverted from a soaring enlightenment to degradation and shame, both the corrupt and the innocent swallowed up by darkness and death.

How do we breathe the same air, drink the same water, and live in such different worlds? Was it truly necessary to name the poor and downtrodden, the ill and disregarded, as our mortal enemies and exclude them from all the beauty and inspiration we enjoy? Couldn’t eugenics have led the more fortunate of us to enhance the lives of those whose mornings were not as full of sunlight and goodness? Do the happy truly need to exterminate the sad to remain happy?

Everybody talked about victory and grand parades, when, in truth, the very notion was impossible. Besides, those of us fortunate enough not to inhabit the Desolation were absolutely terrified by the very idea of it. Nothing but mud and blood for hundreds of miles.

I suppose guilt over the mortal sacrifices of those who fought for us was the root of all this wailing, but really what could be done? Some went to war, while others stayed behind and kept to the eugenical business of attempting to perfect the imperfectible.

Killing on a mass scale is best practiced in an atmosphere of unforgiving partisanship. Who really cares what the enemy thinks is worth dying for so long as their graveyards keep growing and memorials to our own dead become repetitive and indistinct?

“Nearly one hundred thousand people have died in the Desolation this past year, Julian. What could be more deranged than that?”

“Is the death of a hundred thousand more heinous than the death of one? Are we statisticians now? Moral accountants?”

“Julian, my friend, in that one hundred thousand are single deaths, individual human beings with unique hearts and hopes, multiplied one hundred thousand times. There is no true formula for expanding or reducing a great moral dilemma.”

Killing each other, like we do, is mass suicide. The trouble is that we don’t recognize it as such. If we did, perhaps we’d do something about halting this plunge we’re taking into the abyss.

A war passes across the world like rural mowers through fields of grain, putting down to rest what had been grown season to season. Modern cannons performed those old rituals of scythe and plow, gouging rents in the earth, erasing the natural order of things. What grows in the blood and mud? Nothing until we depart. We are not required for life to go on. We just need to leave and not return before balance is regained and the sun can shine on life without men and their endless torments.

When war came across the Fatoma River, forty years after the Great Separation, those simple rural people who had been inhabiting these fertile lands both west and east of the Alban River for quiet centuries were unprepared for the intrusion of hatred and persistent darkness. They were swept away almost entirely in those relentless waves of battery and invasion. No hint of them survives.

Who could know which one of these fellows might be eating his last meal? Across the river were threats from dark corners. Survival depended upon training, yes, of course. Odds increased with perspicacity and teamwork. Still, death had unexpected invitations, and no one could be sure of avoiding that final call.

Where our two-truck convoy drove east, I saw no trees at all. No ruins. No people. No birds. No life. There was nothing but mud clear to the rainy horizon.

Standing alone in the cold drizzling rain, I realized now that this was the Desolation I’d seen in my dreams, a world utterly devoid of life, of anything good to love and nurture and grow. Our wrath had laid waste to this earth and left it barren and cold. One destiny made evident in these putrid fields of the dead.

“These are not moral issues, son. They’re imperatives. Do you understand the distinction?”

“I believe so, sir. You mean that we do what we do, not necessarily because we believe it’s right, but rather to serve our own best interests, whatever they might be.”

“Exactly.”

“If a million people on that side need to die for us to put hot soup on our tables at dinner time, sir, and hot soup is vital to our national survival, we’ll kill a million people.”

Every soldier in our war, or perhaps any war, was a human tragedy. That we tolerate and pursue such profound indignities in this world describes a species in abject failure.

The morbid assembling of casualty figures ended thirty years ago, those numbers already being so enormously obscene as to be considered finally irrelevant, at least in the gilded halls of the Status Imperium whose counting machines had no formula or index for morality.

“To war, where only the vultures are victorious.”

This war has to stop before somebody wins.

REDEMPTION

Is there a world beyond our own where no virtue goes unrewarded, no sin unpunished, whose clear blue skies and sultry evenings are recorded in the Book of Days, and all men seek perfection and immortality of good purpose?

The more miles I traveled out there, the more I became persuaded that survivors were needed more desperately now than heroes. Someone had to outlive all of this so that life could go on and the world might grow and flourish once again.

A people need not be warriors and conquerors to be great. They need only to seek goodness and moral advancement above all else.

Our lives are so brief, why do we trouble each other over trivialities and differences that lead us nowhere? Centuries pass and we are the same as ever, a race in search of a solution to a mystery that has no apparent resolution but whose torments to our sensibilities are ceaseless and cruel. And the wheel rolls on.

Any society so willing and enthusiastic to torture those it deems antithetical to its own purposes must be morally decadent and philosophically adrift. If this was how we lived now, what sort of monsters might we become in decades ahead?

The torments of this war have troubled them greatly for decades. Each medley of injury and betrayal has made peace that haunted fugitive throughout our world. We chase with hope and desperation, Julian, because we have always believed that somewhere what’s unknown to us now will be unveiled in the certain evidence of a better day.

Five hundred and sixty-three miles of unholy cemetery. Irredeemable, unless somehow our hearts are healed. Nothing can change that. One day, children will not remember and then life can proceed anew. But not until then.

If you’re patient, they’ll explain the Republic and how its troubles are not destiny but rather choices that arise in moments of fear and loss of faith in the essential goodness of people.”

I wondered how our hearts perpetrate mythologies that permit us to torment our fellow human beings. What stories do we tell ourselves to feel justified in the evils we pursue? Perhaps the vast black void above the River Philateus was not as great as that which resides in our own souls.

We rebuilt, year after year, rediscovering ourselves in this home of our birth. Labor provided moral and spiritual sustenance. Love and purpose prevailed. A living society untouched by guilt and moral confusion. Six million people thriving on the edge of tomorrow. We say, ‘The sun rises in the east and sets in the west, and the story of our world lies in that cycle.’ We do believe that when we are hand-in-hand with you once more on the shores of the sundown sea, this life will be complete.”

We’ve delved into such blackness of spirit and soul as this world has never seen. Faith in goodness is eroded by the experience of evil, and that cannot stand. We need to divert our course and find that hallowed ground upon which peace can reign once again and tears abate.

There must be hope, dear. And it needn’t appear from the clouds. As we witness these circumstances of our lives, so, too, are we able to form opinions to resolve how we absorb them and choose our way forward. Hope is born from that.

What did we know of this world apart from our madness? To be accustomed to the insanity of mass murder on a scale of great societies would ordinarily be considered unthinkable, a delusion best treated by electrical nodes and institutional therapies. When practiced by the most brilliant minds of a Republic, the unthinkable becomes habit and that habit of cruelty and moral perversion leads the simplest among us to encourage even more heinous acts. Who leads us back to the rawest semblance of virtue and goodness? After a century of despicable contortions, can anyone possibly see an escape from the endless horrors?

More than anyone else I’d known in the metropolis those two skinny boys exemplified the meaning of art and poetry and that vibrant culture of the heart and soul. Naturally they were naïve and silly and pretentious. Isn’t that what art exists for, after all? Daring to express the sins and beauty of the world in such a way that lets somebody, somewhere, dream of another life, a better one?

Cars & Vehicles

Hanley

Algren

Cosmopolitan

Henrouille

Swan

Model Seven

Zane

Jerome

Lyman

Zenith

Royale

Métro

Hüeffer

Argenti

Lancer

Salius

Delaney

weapons-and-inventions

Incandescent artillery shells w/ radioactive phenotheric gas

Incendiary pipes

Borrado 90s

Robots (mechanical men)

Invisible soldiers (corporeal anonymity)

12 Railroad gun

Mechanical rifles

Gas myrmidon guns

Diatomite

Mobile incinerators

Earth mines

Tri-nitrophlogistics

Chloromorphium dart

Suspension tank

Mezentian metals (Lewis, impermeable and edible)

Clothonium particles

Helion gas w/ Méléndré molecules

Morpheus powder

Morphium

Radio rockets

Motor dust inhalers

Oromorphium

VeraForm

Lethereon

Adrenophenotherol

Heliophlogistic Atomized Viridium

Radiophone

Raskol 18 pounder

Stromer-75

Charnel pellets

Music

Glee Club

“Apéritif: May every kiss lead my heart to you"

Violin solo in E minor, “The World in Miniature”

“Will ‘O The Wisp”

Délessért folk music

Farolinese Eight-string mahlousjka and daubha flute

Musical theater: “Love’s Lonely Libretto”

Merkála’s Meridian Quartet, Cadeña Suite in C sharp minor

Reynaldo Font’s Lullaby Suite in B minor

Mascías concertina “For As Long As I Live”

Concerto: Rialto Mecanété’s “Orellia” Movement No. 21

Romaine Royale string and brass combo, “When Eventide Falls” and “Whispering Elms”

Osterhout pulacélu

Pelágie ballad

The Hartley Cummings Banjo Orchestra “Summer Moons”

Book of Song

“Hail Republic”

“Hailing All Saints”

Co-eds singing, “If I were your honey, I’d give you my money and off to the islands we’d fly”

On the Deiopea: “O That Lovely Heart of Heaven”

Freddy whistling, “Dreamy Blue Teardrops”

WRITERS, ARTISTS, BOOKS & GAMES

Pitre Kautsky

Riemer Volgin

Morris Longstreet

“The Last Sonata”

Leandro Porteus architect

“The Aeneid”

Gallinese Book of Hours

“Princess of Mardrus and the Unicorn King” (Atyna)

“Poofus the Cat”

“The Angel and the Dove”

Qantara game and squib books

Jerrold Souza painter

Gustávo Agustín painter

Idel Memphis portrait painter

Strelinsky

McClymonds

Burns

Stassen

Zarité

Alexis Martin

Müsyné dervish

Amphios game

Freyling Villepiqué “Eros and the Owl”

History of the Great Betrayal, “Night Came Walking”

Phanagrams game

Ministrations of Advertising

Dámian poker

Chirographic writing

Lemon socco

Pashlovt oil (black and white)

Gallimard card game

Mary Antoinette and the Snow Queen (Agnes children’s book)

Gypsy Candle (Lewis vs Mary)

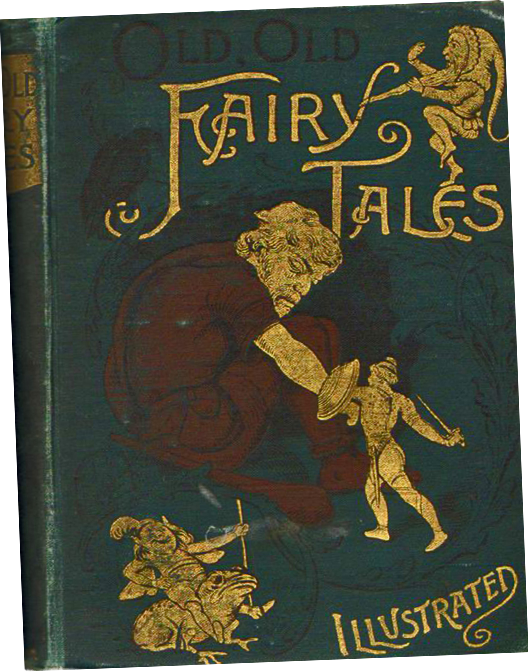

A Child’s Book of Fairy Tales

“Of Gods and Men” - Paul Havrincourt

“Tales Of Christoff Céleste”

Láfhouát adepts

Food & Drink

Kaftak bakery

Pajapiro

Radium-green liquor Sekouz

Blood-red spirit wine Guerrero

Cinnamon Arroussi (buttercorn sauce and meal, Roman mushrooms, sacquali)

Paphus steak (fish)

Boucle poppy

Tomato hash

Sausage and omelette au fromage

Ferésien love potion

Tomato soup Pelotonia

Rahaman salad

Teucrit liquor

Mazzaro tea

Gordoñia cheese

Séverine cheese

Tafra grain

Opis powder

Cafereus champagne

Laval oysters

Askour caviar

Butter cheese wine

Honey cakes

Butter sticks

Jam tarts

Black Tartárean mushrooms

Sapphire Ulla liqueur

Gardash vegetables

Ganpari ham

Honeycakes

Topacchi soup

Sypelle chicken

Alcasian cocoa-coffee

Powdered jelly nouvelle

Cherífa cinnamon tea

Kebir wine

Eggs Kerezza

Hoggari cigarettes

Royal ham

Soulien tea

Xóchitl

Boiled potatoes, cabbage, honeyed carrots “ancién avec marot”

Chocolate petit parc cakes

Rhotean wine (sparkling gold)

Fulton sausage

Eggs Scudéry

Syrup pudding

Honeyberry pudding

Massot tea black

Peach muffin

Scallops in Vironella sauce

Honeygrain biscuits

Jade Morini (liquored syrup)

Ijoujak (lamb stew, spicy taste of curry, cinnamon, pepper, tomato sauce)

Corn muffins

Maldoror beer

Tchäro cigarettes

LeVau sausage

Honey muffins

Nouveau Monde liquor

Rummeled eggs

Péchméja chicken

Rouge-coeur potatoes

Moralis casserole

Libro wine

Spice tea

Beef and noodles “fraternité”

Whipple dry meal (dog food)

SCHOOLS & INSTITUTIONS:

Thayer Hall at Regency College

Porter House Dispensary

Garibaldi Building

Luteroff sanitarium

Fawcett Academy (Freddy elementary school)

Menhennet School (Delia)

Ferdinand Club

Prouter Academy

Templar College (at Sparrow Hill)

McNeely Branson School

Willsford College (Dennett and Paley)

Pellerin Building

Chaude-siérpes ancient cult

Molly Institute (on Simoni Hill)

Ascanius College (Arlo)

Jouhandeau asylum

Salius Academy (Dodd)

Mignard Institute

LeBrunen College (Victor Draxler)

Nieboldt prison

Huegenot College (Dr. Holsendorf drawing Deiopea)

Mollison Institute

Braden College (Simoni Hill)

National Stock Exchange

Selfridge sanitarium

Saturnian faith

Drumont penitentiary

Nationale Club

Mendel Building

Torelli Hall

National Cathedral

Archimbault Cathedral

Organic Medicine Institute

Éspezel Hospital

Flammarion Hospital

Haehnlan Academy (Freddy’s Upper School)

Chapman Hall (Branson)

Tremont Hall (Branson)

Monte Schulz

Monte Schulz, who has been a writer for over forty years, published his first novel in 1990. He then spent ten years writing a thousand page novel of the Jazz Age – published in three parts by Fantagraphics Books (2009–2012). Schulz’s most recent projects include his novel Crossing Eden, published in 2015, and “Seraphonium,” an album and live performance, for which he served as composer, songwriter, and producer. Schulz has been teaching at SBWC since 2001 and became the conference’s owner in 2010.

VIEW PRESS & PR

For interviews, book signings and PR opportunities, please contact:

Deborah Kohan, Partner | Finn Partners

T: +1 212 593 5885

deborah.kohan@finnpartners.com

What Readers Are Saying

What a brilliant combination of suspense, interesting characters, still much to learn about society, etc. Really interesting. Really well written. Masterfully plotted.

It’s a page turner, but also gorgeously written. Very exciting. Endless twists and turns.

It’s just so fully formed and expansive, it’s remarkable. It’s as beautifully written as everything you do but also completely different... also just loved the details and richness of the descriptive language in building the world.

The book is like several different books/genres in one – the grim naturalism of the Desolation, the gorgeous fantasy of the Elysium section.

Monte Schulz's Metropolis is a stupendously imaginative epic that wrestles with some of the thorniest subjects still plaguing humanity today (war, xenophobia, disease, fascism) through the lens of a fantastical quasi-European early 20th C. This is a sly mystery tale nestled inside a moving love story, all wrapped up in a war torn dystopia. Imagine China Mieville's The City & The City crossed with Susannah Clarke's Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, and smattering of Lars Von Trier's film Europa.